Vijay Reddy, Human Sciences Research Council; Crain Soudien, Human Sciences Research Council, and Lolita Desiree Winnaar, Human Sciences Research Council

By mid April about 1.725 billion students globally had been affected by the closure of school and higher education institutions in response to the coronavirus pandemic. According to the UNESCO Monitoring Report, 192 countries have implemented nationwide closures, affecting about 99% of the world’s student population.

This is unprecedented. The scale and complexity of what’s happening is entirely new territory.

In recent decades crises such as natural disasters, armed conflicts and epidemics have disrupted education around the world. For example, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina in the US destroyed 110 of New Orleans’ 126 public schools. In the past decade, at least 2.8 million Syrian children have been out of school for some period, and in 2013, 5 million children were out of school as a result of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa.

School closures affect students, teachers and families and have far-reaching economic and social effects. This is especially the case for fragile education systems and the negative effects will be more severe for disadvantaged learners and their families.

Finding alternative learning forms during this time is difficult. But not impossible.

In response to COVID-19 school closures and adherence to social distancing, UNESCO and many governments and agencies have recommended the use of distance learning, open educational applications and online learning to reduce disruption to education.

Richer households are better placed to sustain learning through online learning strategies, although with a lot of effort and challenges for teachers and parents. In poorer households many children don’t have a desk, books, internet connectivity, a computer, or parents who can take the role of homeschooling. The disparity in access to digital devices and connectivity between rich and poor is immense.

Read more: How South Africa can address digital inequalities in e-learning

While it’s necessary to institute educational programmes during this period, these will not replace regular school. Despite the best efforts of government, schools and parents there will be learning losses for almost everybody and worsened educational outcomes for the poor.

We applied the learning curve scenario methodology developed by the World Bank to the South African Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study data to illustrate the patterns of expected learning losses over the next few months due to school closures and disruptions.

Possible education outcomes

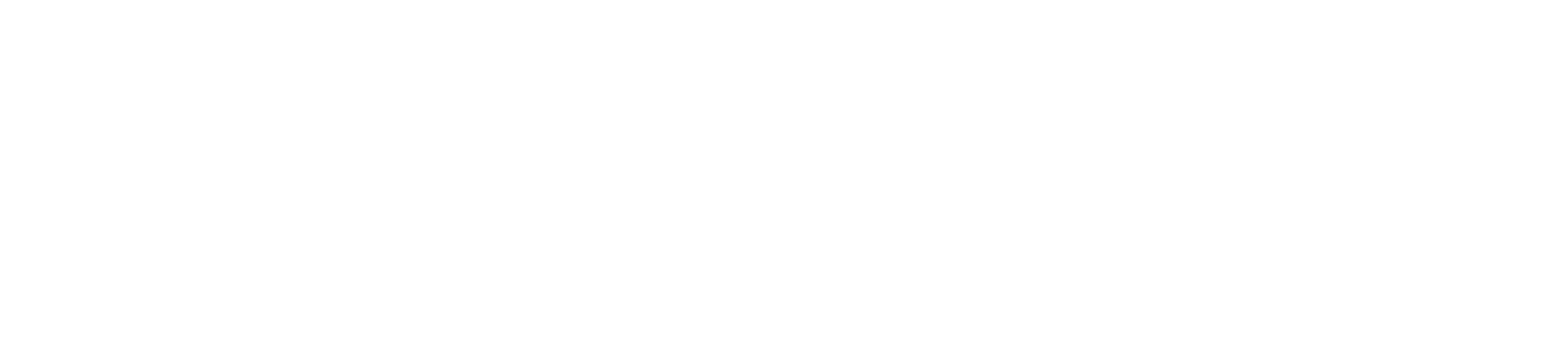

We plotted the kernel density learning curves for the 2015 study scores and a (hypothetical) reduced learning average across the distribution. We then plotted the kernel density curves for the fee-paying and no-fee schools and the reduced learning averages for each.

We expect higher learning losses in no-fee schools. While we don’t know the exact value of the learning losses, these graphs illustrate that learning loss patterns will be different for learners in different school types.

In graph A the solid line shows the South African learner mathematics achievement. The dotted line shows learner achievement profile because of learning losses. Graph B shows the expected learning graphs for current achievement and expected reduced achievement in no-fee and fee-paying schools.

We use the cut-off score of 300 to show the numbers of poorly achieving learners. The shaded portions in these graphs show the increased proportion of learners achieving very low achievement scores. The existing data show a larger proportion of learners in no-fee schools obtaining scores below the 300 point cut-off compared to learners in fee-paying schools.

Our findings underscore the fact that disasters amplify the existing structural inequalities in society and worsen inequalities through an unequal recovery process.

Going forward

Parental and family support is important during this period. Parents and family must consciously and deliberately support children in completing a few hours of school work. A Human Sciences Research Council study on early educational environments found that close to one third of parents reported that they read books to their children and played with alphabets, number toys and word games.

Half of them reported that they wrote numbers, watched educational TV and sang songs with their children. The patterns are different for learners in fee and no-fee schools. But home activities are happening and parents must be supported and encouraged to continue with educational activities.

It’s also important to start preparing for the recovery period when schools reopen. The curriculum must be simplified, targeting areas where learning loss will be most consequential for the following years. The sad and uncomfortable truth is that for South Africa, with low and unequal achievement scores, the longer social distancing is in place the bigger the learning losses for learners, especially the most disadvantaged, thereby deepening inequalities.

Vijay Reddy, Distinguished Research Specialist, Human Sciences Research Council; Crain Soudien, Chief Executive Officer of the Human Sciences Research Council, Human Sciences Research Council, and Lolita Desiree Winnaar, Senior Research Specialist, Education and Skills Development, Human Sciences Research Council

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.